An open wound

"A pomegranate can sustain you for a year, as long as you only eat a kernel per day."

Starvation was widely used in the deportation and mass murder of Armenians in the last century. According to Armenian legend, many Armenians survived the long marches through the desert by hiding pomegranates in their clothes when they were being deported by force during the years 1915 to 1920.

“It is said that a pomegranate contains 365 kernels, and according to myth, that was enough to keep a family alive”, says Lene Wetteland, who works for the NGO Norwegian Helsinki Committee. She has worked with Armenian issues for many years. She says the pomegranate has become an important symbol for Armenians today.

"The Armenians have a painful history of food shortages and deadly starvation, so it is important for them to keep the dinner table so abundant that it is not possible to finish it all. The guest is expected to leave some of the food. "

Food as a weapon

What is known today as the Armenian genocide took place during the First World War. Many Armenians were executed, deported by force or starved to death in the years between 1915 and 1920. The exact death toll is uncertain, but some estimate that 1,5 million Armenians perished.

Christian Armenians had lived side by side with Turks, Kurds and other peoples in the Ottoman Empire, where Turkey is today. When the patriotic organisation “The Young Turks” took power in Turkey, they gradually introduced anti-Armenian policies. The Armenians and other Christian minorities were seen as obstacles to the religious unity of Turkey. They were subjected to more and more oppression and discrimination. On April 24, 1915, 250 intellectuals and other prominent people were arrested by the authorities, and later died during their deportation. This is considered the starting point of the genocide.

“Armenian men were either executed outright or used as slave laborers in the construction of Turkey’s new railway from Constantinople (Istanbul) to Baghdad”, says Wettland. The working conditions were so brutal that many died along the tracks.

Women and children were deported and sent on long marches on foot out into the Syrian desert. “These masses of people were deliberately forced out without food or drink”, says Wetteland.

“There are many eyewitness accounts from this time describing the gruesome scenes. The accounts tell of mothers selling their children for bread. Not necessarily for their own survival, but in the hopes that their children would get a better life”, Wetteland explains.

There were many attempts to help the emaciated people who marched through the desert. Both local citizens, diplomats, missionaries, and engineers put themselves in harms way to reach the Armenians with food supplies. One group of German engineers bought large supplies of bread, but were stopped by Kurdish and Turkish officials. The result was that many of those who were deported died from starvation, disease or from the harsh desert conditions.

Eyewitness accounts and letters described how women were killed in other ways, besides starvation. Wetteland explains how women were allegedly bound and thrown into rivers, or trapped in caves, where they were poisoned by smoke. Many are also said to have been sold as slaves or forced into marriage. Some reluctantly made the choice to marry, in the hopes that they, and their children, would have a better life.

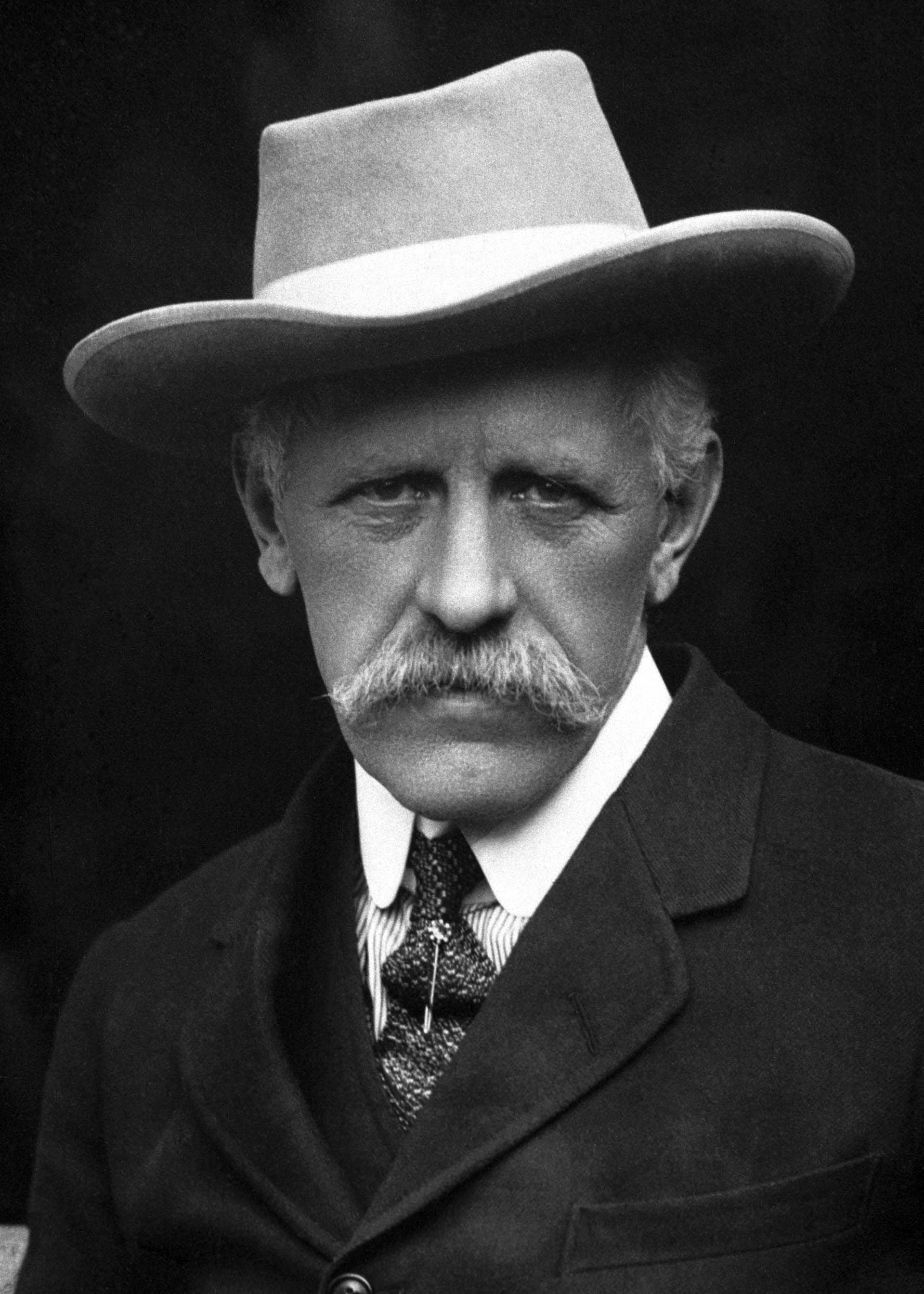

Fridtjof Nansen in Armenia

In the aftermath of the genocide, the Norwegian Fridtjof Nansen played an important role in helping the surviving Armenians. He established the so-called “Nansen passport”, which gave paperless Armenians the opportunity to flee to other countries. In 1922, Nansen was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize for his humanitarian work. Nansen is still highly regarded in Armenia, and there are both boulevards and men named after the Norwegian explorer.

Half a million Armenians managed to flee, either to the Middle East, Europe, or The United States. Today, millions of descendants of the survivors of the genocide live in other countries than Armenia. Armenia’s land area is far smaller today than it used to be, and has a population of about three million.

A contested genocide

Few people doubt that the deportation and murder of thousands of Armenians in this period took place. Still, whether the events should be classified as a genocide or not, is still a contested question. Today, only around thirty countries have chosen to acknowledge the events as a genocide. Norway is not among these. Some academics also avoid the term.

Some Armenians are working to rectify what they see as a failure to acknowledge a historical fact. The most prominent of these is mega-celebrity Kim Kardashian, who is of Armenian descent. She and her supporters petitioned the U.S. House of Representatives, and in 2019, the House publicly condemned the events. In April 2021, US President Joe Biden used the term genocide to describe the extermination of the Armenians.

The government of Turkey puts pressure on countries who acknowledge the events as a genocide. Turkish authorities claim that the events were a consequence of the war, and that the food shortages were generally high among all ethnic groups in this period. It is also claimed that many Armenians collaborated with the Russians.

There are examples of the Turkish government going to great lengths to keep the events from gaining public attention. In 2016, they tried to stop the screening of “The Promise”, a Hollywood movie telling the story of young Armenians immediately before the genocide began.

Listen to history

Armenia in the Nobel Peace Prize Exhibition 2020

When this year’s Peace Prize exhibition was created, we wanted to show how food is being used as a weapon in war and conflict. The renowned Ethiopian photographer Aïda Muluneh was commissioned to create ten works, illustrating ten different countries and conflicts where food has been used as a tool of power. The photo about Armenia is called "An Open Wound". In the vide below, the artist explains the story behind the photo:

Share: